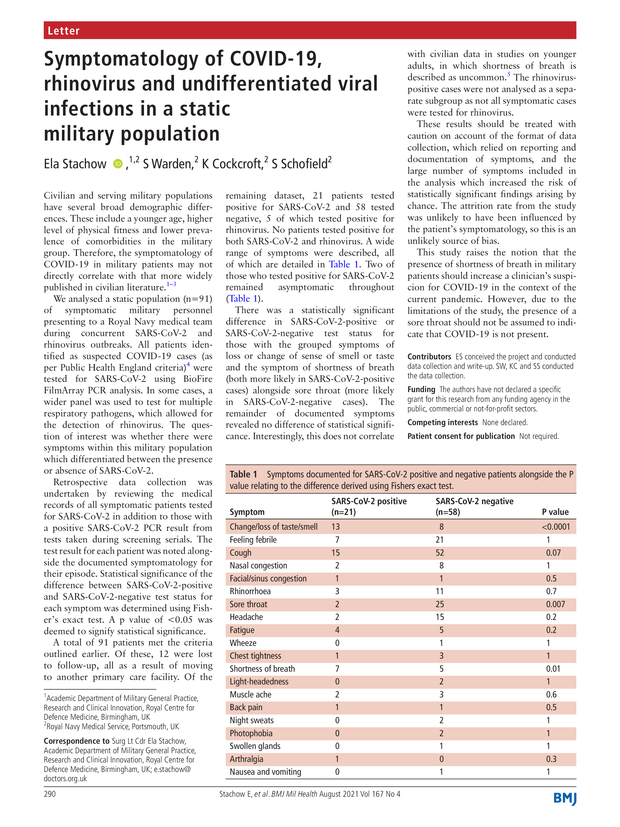

Article Text

Letter

Symptomatology of COVID-19, rhinovirus and undifferentiated viral infections in a static military population

Statistics from Altmetric.com

You do not have access to the full text of this article, the first page of the PDF of this article appears above.