Abstract

Aims

To determine the prevalence of comorbid probable post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol misuse in a UK military cohort study and to determine the level of co-occurrence between these disorders; further aims were to investigate the association between alcohol misuse and the different PTSD symptom clusters, and to assess what factors are associated with probable PTSD in participants with alcohol misuse.

Methods

Data from 9984 participants of Phase 2 of the health and well-being survey of serving and ex-serving members of the UK Armed Forces were assessed for probable PTSD and alcohol misuse using the PTSD checklist (PCL-C) and the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT), respectively.

Results

1.8 % [95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.5–2.1] of the sample met the criteria for both PTSD and alcohol misuse. All three symptom clusters of PTSD were significantly associated with alcohol misuse, with similar odds ranging from 2.46 to 2.85. Factors associated with probable PTSD in individuals reporting alcohol misuse were age [ages 30–34 (years): OR 2.51, 95 % CI 1.15–5.49; ages 40–44 years: OR 2.77, 95 % CI 1.18–6.47], officer rank (OR 0.36, 95 % CI 0.16–0.85), being in a combat role in parent unit (OR 1.99, 95 % CI 1.20–3.31) and common mental disorder (CMD) (OR 21.56, 95 % CI 12.00–38.74).

Conclusions

This study provides strong evidence that PTSD and alcohol misuse are often co-occurring. CMD was highly associated with probable PTSD in individuals with alcohol misuse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcohol misuse are both potentially debilitating disorders, and the association between the two is well established [1–3]. Hazardous alcohol use or dependence is the most common comorbidity in males with PTSD [2], and the estimated prevalence of alcohol use disorders in individuals with PTSD is higher than that of the general population [4]. The association between PTSD and alcohol misuse has been evidenced across a number of countries [5–8]. A UK study found that 38.5 % of individuals with a substance use disorder (including alcohol) met DSM-IV criteria for current PTSD [9]. Results from the US National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) report a prevalence of PTSD of 10.3 % in men and 26.2 % in women who have alcohol dependence/misuse in the US general population, while the risk of developing alcohol dependence in those with previous PTSD was 2.67 and 3.37 times greater in men and women, respectively [10]. In the more recent NCS-replication, PTSD was associated with a higher risk (approximately four times the odds) of both alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse [11]. There is evidence for this comorbidity in studies of military personnel [3, 12, 13]. Alcohol misuse and PTSD also share common risk factors, for example combat exposure [14, 15], childhood adversity [16, 17] and common mental disorder [18, 19].

Whilst the association between PTSD and alcohol misuse has been established, the direction of causation is unknown. Several studies suggest that the comorbidity between alcohol misuse and PTSD represents an attempt at self-medication to alleviate the severity of PTSD-related symptoms [20–22], and that the development of new alcohol disorders in military personnel is uniquely predicted by higher levels of PTSD symptom severity [23]. It has also been found that substance-misuse patients with PTSD relapse more often and more quickly than those without comorbid PTSD [24, 25] and it has been suggested that such relapses are a response to resurgent PTSD symptoms [26]. Alternatively, alcohol misuse could be a risk factor for the development of PTSD. Davidson et al. found that alcohol misuse preceded PTSD by 3.1 years in a sample of US Vietnam veterans [27], and alcohol misuse may be associated with an increased rate of traumatisation due to the association between alcohol use and accidents and violence [28].

There is also evidence that particular PTSD symptoms are more strongly related to alcohol misuse than others; several studies suggest that avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms are more strongly associated with substance misuse in general [29], and specifically with alcohol misuse [30–33]. Another recent study, of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, found that emotional-numbing symptoms of PTSD (a subset of the avoidance symptoms) were independently related to hazardous drinking in female veterans [34].

Several other studies have focussed on military veterans, with findings suggesting that US military personnel are at a higher risk of developing both alcohol misuse [35] and PTSD [36] than the general population. Studies from the UK also show higher rates of alcohol misuse in the military [37], but suggest that the prevalence of PTSD is similar to that in the general population [38, 39]. Whilst UK military studies have shown a strong association between PTSD and alcohol [18], the current study offers the opportunity to explore this relationship further. This study aims (1) to assess the comorbidity of PTSD and alcohol misuse in UK military personnel, (2) to determine the association of alcohol misuse with the three symptom clusters of PTSD, and (3) to examine what factors are associated with PTSD in those individuals who meet the criteria for alcohol misuse after accounting for current common mental disorders.

Method

Study design and participants

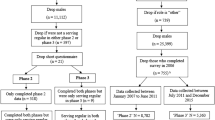

This study uses data gathered as part of Phase 2 of the health and well-being survey of serving and ex-serving members of the UK Armed Forces [38, 40]. This study collected data via self-complete questionnaires. Phase 1 of the survey was carried out between 2004 and 2006 [40], assessing the physical and mental health of the UK Armed Forces, comprising two samples. The first, termed the TELIC sample (the codename for the 2003–2009 UK military presence in Iraq), included personnel who deployed to Iraq between January 18, 2003, and April 28, 2003, and consisted of approximately 10 % of the fighting force deployed at that time. The second group, termed the Era sample, comprised individuals who were in the military during the same period, but were not at that time deployed to Iraq. In total, 10,272 participants completed the Phase 1 questionnaire (response rate 59 %).

Phase 2 of the survey used a modified version of the Phase 1 questionnaire, with data collection occurring between 2007 and 2009. Participants from Phase 1 were re-contacted, with 6429 individuals (response rate 68.4 %) completing the Phase 2 questionnaire (now termed the follow-up sample). Two new samples were also included. The first was a random sample of personnel deployed to Afghanistan on operation HERRICK (the UK military codename for operations in Afghanistan) at any time between April 2006 and April 2007. 896 individuals (response rate 50.1 %) in this sample completed the Phase 2 questionnaire. The second new sample, termed the replenishment sample, included individuals who had joined the military since recruitment for Phase 1 in 2003, and had the opportunity to deploy on either TELIC or HERRICK during the study period. This sample was randomly drawn from those who joined the trained strength between April 2003 and April 2007, and 2665 individuals (response rate 40.2 %) completed the questionnaire. In total, 9990 individuals completed the Phase 2 questionnaire (overall response rate 56.0 %). Of these, six were later removed as they were found to be ineligible, resulting in 9984 individuals in the final sample (Fig. 1).

The socio-demographic characteristics of the Phase 2 sample were compared with the composition of the UK military (at April 2007), to ensure the sample was representative [38]. The distribution of sex, age, engagement type and rank was similar between groups, with service being the only exception; the sample included proportionally more army personnel than the UK military as a whole in 2007 (67 and 56 % respectively).

All participants were identified by Defence Analytical Services and Advice (DASA), UK Ministry of Defence (MoD), and ethical approval was provided by the King’s College Hospital local research ethics committee, and the MoD Research Ethics Committee (MODREC).

Measures

To assess alcohol misuse, the Phase 2 questionnaire utilised the 10-item World Health Organization (WHO) alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) [41]. The AUDIT assesses levels of alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence and negative consequences of alcohol abuse, in the previous 12 months. For the purposes of this study, participants were classified as reporting ‘alcohol misuse’ if they scored 16 or above. This cut-off is higher than that commonly used in the general population, and is defined by the WHO as ‘hazardous use that is also harmful to health’ [41].

For the assessment of PTSD symptoms, the Phase 2 questionnaire used the National Centre for PTSD Checklist—Civilian version (PCL-C) [42]. This is a 17-item questionnaire, and a cut-off of 50 or more was used to define caseness (‘probable PTSD’). Each question is rated on a scale from 1 to 5 depending on how often the individual has ‘been bothered by these problems’ in the past month, with 1 being ‘not at all’ and 5 being ‘extremely’.

The PCL-C can be divided into three PTSD symptom clusters [43], with 5 of the 17 questions assessing ‘re-experiencing’, 7 ‘avoidance’, and 5 ‘hyperarousal’ symptoms, corresponding to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria [44]. A rating of 4 or above (indicating the participant has been moderately bothered by that problem in the past month) was considered a positive response for that symptom being present. In order to determine caseness for the three symptom clusters, the following criteria were used: the ‘re-experiencing’ cluster required 1 or more positive symptom responses, the ‘avoidance’ cluster 3 or more positive symptom responses and the ‘hyperarousal’ cluster 2 or more positive symptom responses [43].

Symptoms of common mental disorder (CMD) including somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction and depression were measured using the General Health Questionnaire 12 (GHQ-12) [45]. This assessed symptoms of CMD in ‘the last few weeks’, with caseness defined as a score of 4 or above (out of a possible 12) [46].

Two measures were used to assess childhood adversity [47], which were adapted from the Adverse Childhood Exposure study scale [48]. The first measured childhood family relationship adversity, by means of four positive items that were negatively scored (e.g., “I came from a close family”), and four negative items (e.g., “I used to be hit/hurt by a parent or caregiver regularly”) [47]. The scores for these eight items were summed to form a cumulative measure, and analysed as 0, 1 or 2+ adversities. The second measure assessed childhood antisocial behaviour, and was deemed positive if the participant a) answered ‘true’ to “I used to get into physical fights at school”, and b) answered true to one of the following: “I often used to play truant at school”; “I was suspended or expelled from school”; or “I did things that should have got me (or did get me) into trouble with the police” [49].

Age at Phase 2 questionnaire completion (in years), sex and marital status (single; married/cohabiting/in a relationship; separated/widowed/divorced) were assessed, as well as rank (commissioned officers; non-commissioned officers and other ranks), engagement type (regular or reservist), most recent deployment (Iraq; Afghanistan; no deployment) and whether the individual deployed in a combat role.

Data analyses

Prevalence and comorbidity

The prevalence of probable PTSD and alcohol misuse were determined, and individuals meeting the criteria for both disorders were classified as comorbid.

Alcohol misuse and probable PTSD/PTSD symptom clusters

Logistic regression was used to determine the association between alcohol misuse and probable PTSD, as well as between alcohol misuse and the three PTSD symptom clusters. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) [adjusted for socio-demographic and military factors—sex, age, marital status, rank, last deployment and engagement type (regular/reservist)] were calculated.

Factors associated with PTSD in individuals reporting alcohol misuse

Logistic regression was performed to determine the association between various socio-demographic/military factors (sex, age, marital status, military status, rank, last deployment, combat role, childhood adversity and common mental disorder) and probable PTSD within the alcohol misuse group. Unadjusted and adjusted ORs (and 95 % CIs) were calculated.

Although we have looked at the prevalence of PTSD in those scoring positively for alcohol misuse, the low overall prevalence of participants scoring positive for probable PTSD prevented us from having the statistical power to investigate what factors were associated with alcohol misuse in the PTSD group.

All analyses were performed using the statistical software programme STATA (version 11.0) [50]. All reported frequencies are unweighted, but percentages, odds ratios (ORs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) are weighted to account for sampling fractions and probability of response [38]. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

The majority of participants were male, in a relationship, under the age of 40 years, regulars of non-commissioned officer (NCO) or other rank, and more than half reported no previous deployment to either Iraq or Afghanistan (Table 1). A quarter of the sample reported that they were in a combat role in their parent unit. More than half of the sample reported at least one family relationship adversity in childhood and 17 % met the criteria for childhood antisocial behaviour. A fifth of the sample met the criteria for a CMD and 4 % met criteria for probable PTSD.

Prevalence and comorbidity

376 participants [4.0 % (95 % CI 3.5–4.5)] were defined as having ‘probable PTSD’, with 1323 participants [13.0 % (95 % CI 12.3–13.8)] defined as reporting alcohol misuse. 1.8 % (95 % CI 1.5–2.1) of participants (n = 159) scored above threshold on both measures, and 84.8 % (95 % CI 83.4–85.6) did not score positive for either condition (n = 8251). In the group reporting probable PTSD, 44.9 % (95 % CI 0.4–0.5) had comorbid alcohol misuse, and within the group defined as reporting alcohol misuse, 13.6 % (95 % CI 0.1–0.2) also reported probable PTSD.

Alcohol misuse and probable PTSD/PTSD-symptom clusters

Rates of probable PTSD were assessed in those who scored positive for alcohol misuse, and those who did not. Those scoring positive for alcohol misuse showed an approximate threefold increase in odds of having probable PTSD, compared to those without alcohol misuse (Table 2).

All three PTSD symptom clusters were significantly associated with alcohol misuse compared to those without alcohol misuse, with a two- to threefold increase in odds for each cluster (Table 2).

Factors associated with PTSD in the alcohol misuse group

The association between probable PTSD and various socio-demographic and military factors were examined in the group meeting the criteria for alcohol misuse. Individuals aged 30–34 years, and those aged 40–44 years, showed an approximate two- to threefold increase in odds for probable PTSD (compared to the reference category of participants aged 18–24 years) (Table 3). Officers had reduced odds of PTSD compared to non-commissioned officers and other ranks. Participants who were in a combat role in their parent unit showed a twofold increase in odds compared to participants in a non-combat role. The most strongly associated factor was CMD, with individuals scoring positive for CMD showing a 20-fold increase in odds for probable PTSD compared to those who did not. This may to a large extent be explained by the strong association between PTSD and CMD (results available from authors).

Discussion

This study has established that the prevalence of comorbid PTSD and alcohol misuse in the UK military is 1.8 %, with 44.9 % of those with probable PTSD reporting alcohol misuse, and 13.6 % of those with alcohol misuse also meeting the criteria for PTSD. We found that all three symptom clusters of PTSD were reported significantly more often in those with alcohol misuse than those without. In those reporting alcohol misuse, we found a strong significant association between PTSD and CMD, as well as significant associations with age, rank and combat role.

This study found that the prevalence of probable PTSD within the group scoring positive for alcohol misuse was 13.6 %. This is slightly less than previous studies have found, with the rate of PTSD in those with alcohol misuse commonly reported as 15–30 % [51–53] and sometimes greater than 50 % [54]. However, 13.6 % is still higher than the prevalence of PTSD in the general military population (4 %), suggesting a strong association between the two disorders.

All three PTSD symptom clusters were strongly associated with alcohol misuse, and this study does not support previous findings that the ‘avoidance’ cluster of symptoms was more strongly associated with alcohol misuse [29–33, 55]. Our findings are in line with those of Johnson [56] and Taft [57], who found that all three symptom clusters were similarly (and significantly) associated with alcohol misuse.

In those individuals who met the criteria for alcohol misuse, there was a statistically significant association between combat role and PTSD. This fits with other military studies which have found higher rates of PTSD in those deployed in a combat role [58]. The strongest association, however, was found between CMD and PTSD (in those with alcohol misuse). This may be a result of the well-established associations between substance misuse, PTSD and depression [59–61]. A number of recent studies have looked at the interplay between these factors. A recent meta analysis found that 52 % of those with PTSD had comorbid major depressive disorder [19]. Khoury et al. found that PTSD symptom scores in a lifelong alcohol-dependent group were no longer significantly different from non-dependents once depressive symptoms were controlled for [33]. Similarly, other studies have found that the PTSD risk in those with alcohol misuse is no longer significant when adjusted for depression risk [61], and that depression is significantly associated with PTSD and alcohol misuse comorbidity [62].

The present study found no significant association between childhood adversity and PTSD in those reporting alcohol misuse. This is counter to the findings of several studies [63, 64], including those using samples drawn from both the UK [47] and US military populations [65, 66]. There may be other childhood or pre-enlistment risk factors for PTSD which we were not able to measure in the current study and there is potential for an interaction between childhood adversity and combat exposure, with a greater PTSD risk in those exposed to combat who had already experienced traumatic events in childhood [66].

Study strengths and limitations

Most studies looking at PTSD and alcohol misuse in military populations have focussed on the US Armed Forces, and by drawing data from the UK military, this study has broadened the scope of research in this field. This study also investigated the three symptom clusters of PTSD separately, a distinction not made in all research. Furthermore, although all data were gathered using a self-report method, the measures included in the questionnaire (e.g., AUDIT, PCL-C) have well-established reliability and validity.

There are various aspects of the association between alcohol abuse and PTSD that are not addressed in this study. Although we have looked at the prevalence of PTSD in those scoring positively for alcohol misuse, the low overall prevalence of participants scoring positive for probable PTSD prevented us from having the statistical power to investigate what factors were associated with alcohol misuse in the PTSD group. Also, some studies separate the ‘avoidance’ cluster of PTSD symptoms into two groups—‘avoidance’ symptoms and ‘numbing’ symptoms—and they suggest it is the ‘numbing’ symptoms that are more strongly associated with alcohol misuse [67, 68]. By not dividing the ‘avoidance’ cluster this association could potentially be missed. This distinction was not made in the present study, due to the low reported prevalence of PTSD in our sample. Further this study was based on the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD using the PCL. Recently with the introduction of the DSM-V criteria, the three symptom clusters (intrusive recollections, avoidant/numbing symptoms, and hyper-arousal symptoms) have been replaced by four symptom clusters (intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity). It will be essential that the revised criteria are explored in subsequent studies which use the PCL-5.

Implications

Although the majority of military personnel do not report alcohol misuse or PTSD, this study has demonstrated that PTSD and alcohol misuse do co-occur with approximately 50 % of those with probable PTSD also reporting alcohol misuse. This has implications for clinicians who should ensure that individuals presenting with either condition are assessed for comorbidity. Therefore, treatment for PTSD should take the alcohol misuse into account rather than treating the conditions consecutively. This might help identify the cause of their initial presentation (e.g., heavy drinking to alleviate the symptoms of undiagnosed PTSD), and in turn lead to more effective treatment and counselling programs. The role of CMD is also important to consider as some individuals reported all three conditions, this level of co-morbidity is likely to impact on presentation and treatment priorities. However, these cross-sectional results do not clarify the direction of the association.

Conclusion

The present study has demonstrated the co-occurrence of alcohol misuse and PTSD in the UK military and provides further evidence that other factors, most notably CMD, are also associated with this comorbidity.

References

McFarlane AC (1998) Epidemiological evidence about the relationship between PTSD and alcohol abuse: the nature of the association. Addict Behav 23(6):813–825. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00098-7 (published online first: epub date)

Stewart SH (1996) Alcohol abuse in individuals exposed to trauma: a critical review. Psychol Bull 120(1):83–112

Debell F, Fear N, Head M et al (2014) A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014:1–25. doi:10.1007/s00127-014-0855-7 (published online first: epub date)

Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB (1995) Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52(12):1048–1060

Driessen M, Schulte S, Luedecke C et al (2008) Trauma and PTSD in patients with alcohol, drug, or dual dependence: a multi-center study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32(3):481–488

Kozaric-Kovacic D, Ljubin T, Grappe M (2000) Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence in displaced persons. Croat Med J 41(2):173–178

Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Peters L (2006) Trauma, PTSD, and substance use disorders: findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Am J Psychiatry 163(4):652–658

Wang H, Jin H, Nunnink SE et al (2011) Identification of post traumatic stress disorder and risk factors in military first responders 6 months after Wen Chuan earthquake in China. J Affect Disord 130(1–2):213–219

Reynolds M, Mezey G, Chapman M, Wheeler M, Drummond C, Baldacchino A (2005) Co-morbid post-traumatic stress disorder in a substance misusing clinical population. Drug Alcohol Depend 77(3):251–258

Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC (1997) Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54(4):313–321

Hofmann SG, Richey JA, Kashdan TB, McKnight PE (2009) Anxiety disorders moderate the association between externalizing problems and substance use disorders: data from the National Comorbidity Survey-revised. J Anxiety Disord 23(4):529–534

Kline A, Weiner MD, Ciccone DS, Interian A, Hill LS, Losonczy M (2014) Increased risk of alcohol dependency in a cohort of National Guard troops with PTSD: a longitudinal study. J Psychiatr Res 50:18–25. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.11.007 (published online first: epub date)

Kehle SM, Ferrier-Auerbach AG, Meis LA, Arbisi PA, Erbes CR, Polusny MA (2012) Predictors of postdeployment alcohol use disorders in National Guard soldiers deployed to Operation Iraqi Freedom. Psychol Addict Behav J Soc Psychol Addict Behav 26(1):42–50. doi:10.1037/a0024663 (published online first: epub date)

Jacobson IG, Ryan MK, Hooper TI et al (2008) ALcohol use and alcohol-related problems before and after military combat deployment. JAMA 300(6):663–675. doi:10.1001/jama.300.6.663 (published online first: epub date)

Fear NT, Jones M, Murphy D et al (2010) What are the consequences of deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan on the mental health of the UK armed forces? A cohort study. Lancet 375(9728):1783–1797

Iversen AC, Fear NT, Simonoff E et al (2007) Influence of childhood adversity on health among male UK military personnel. Br J Psychiatry 191(6):506–511

Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ et al (2002) Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatric Serv 53(8):1001–1009. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.53.8.1001 (published online first: epub date)

Jones M, Rona RJ, Hooper R, Wessely S (2006) The burden of psychological symptoms in UK Armed Forces. Occup Med 56(5):322–328. doi:10.1093/occmed/kql023 (published online first: epub date)

Rytwinski NK, Scur MD, Feeny NC, Youngstrom EA (2013) The co-occurrence of major depressive disorder among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. J Trauma Stress 26(3):299–309. doi:10.1002/jts.21814 (published online first: epub date)

Khantzian EJ (1985) The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Psychiatry 142(11):1259–1264

Stewart SH (1997) Trauma memory and alcohol abuse: drinking to forget? Recollections of trauma: scientific evidence and clinical practice. Plenum Press, New York, pp 461–467

Lacoursiere RB, Godfrey KE, Ruby LM (1980) Traumatic neurosis in the etiology of alcoholism: Viet Nam combat and other trauma. Am J Psychiatry 137(8):966–968

Kehle SM, Ferrier-Auerbach AG, Meis LA, Arbisi PA, Erbes CR, Polusny MA (2012) Predictors of post deployment alcohol use disorders in National Guard soldiers deployed to operation Iraqi freedom. Psychol Addict Behav 26(1):42

Brown PJ, Recupero PR, Stout R (1995) PTSD substance abuse comorbidity and treatment utilization. Addict Behav 20(2):251–254

Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR (2001) Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry 158(8):1184–1190. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1184 (published online first: epub date)

Brady KT, Killeen T, Saladin ME, Dansky B et al (1994) Comorbid substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder: characteristics of women in treatment. Am J Addict 3(2):160–164. doi:10.3109/10550499409117249 (published online first: epub date)

Davidson JRT, Kudler HS, Saunders WB, Smith RD (1990) Symptom and comorbidity patterns in World War II and Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Compr Psychiatry 31(2):162–170. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(90)90020-S (published online first: epub date)

Cottler LB, Compton IWM, Mager D, Spitznagel EL, Janca A (1992) Posttraumatic stress disorder among substance users from the general population. Am J Psychiatry 149(5):664–670

Saladin ME, Brady KT, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG (1995) Understanding comorbidity between PTSD and substance use disorders: two preliminary investigations. Addict Behav 20(5):643–655

Back SE, Sonne SC, Killeen T, Dansky BS, Brady KT (2003) Comparative profiles of women with PTSD and comorbid cocaine or alcohol dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 29(1):169–189

Stewart SH, Conrod PJ, Pihl RO, Dongier M (1999) Relations between posttraumatic stress symptom dimensions and substance dependence in a community-recruited sample of substance-abusing women. Psychol Addict Behav 13(2):78–88. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.13.2.78 (published online first: epub date)

Hien DA, Campbell ANC, Ruglass LM, Hu M-C, Killeen T (2010) The role of alcohol misuse in PTSD outcomes for women in community treatment: a secondary analysis of NIDA’s Women and Trauma Study. Drug Alcohol Depend 111(1–2):114–119

Khoury L, Tang YL, Bradley B, Cubells JF, Ressler KJ (2010) Substance use, childhood traumatic experience, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in an urban civilian population. Depress Anxiety 27(12):1077–1086

Scott JC, Pietrzak RH, Mattocks K, Southwick SM, Brandt C, Haskell S (2013) Gender differences in the correlates of hazardous drinking among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Drug Alcohol Depend 127(1–3):15–22

Killgore WDS, Cotting DI, Thomas JL et al (2008) Post-combat invincibility: violent combat experiences are associated with increased risk-taking propensity following deployment. J Psychiatr Res 42(13):1112–1121. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.001 (published online first: epub date)

Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS (2006) Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. doi:10.1001/jama.295.9.1023 (published online first: epub date)

Fear NT, Iversen A, Meltzer H et al (2007) Patterns of drinking in the UK armed forces. Addiction 102(11):1749–1759. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01978.x (published online first: epub date)

Fear NT, Jones M, Murphy D et al (2010) What are the consequences of deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan on the mental health of the UK armed forces? A cohort study. Lancet 375(9728):1783–1797

McManus S, Meltzer H, Brugha T, Bebbington P, Jenkins R (2009) Adult psychiatric morbidity in England, 2007: results of a household survey. National Centre for Social Research, London

Hotopf M, Hull L, Fear NT et al (2006) The health of UK military personnel who deployed to the 2003 Iraq war: a cohort study. Lancet 367(9524):1731–1741

Babor FT, Biddles-Higgins JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG (2001) AUDIT: the alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary care, 2nd edn. World Health Organization, Geneva

Weathers FW, Huska JA, Keane TM (1991) The PTSD checklist-civilian version (PCL-C). Boston Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Boston

Buckley TC, Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ (1996) A prospective examination of delayed onset PTSD secondary to motor vehicle accidents. J Abnorm Psychol 105(4):617–625

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

Goldberg D, Williams P (1988) User’s guide to the GHQ. NFER-Nelson, Windsor

Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N et al (1997) The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med 27(01):191–197

Iversen AC, Fear NT, Simonoff E et al (2007) Influence of childhood adversity on health among male UK military personnel. Br J Psychiatry 191:506–511

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D et al (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 14(4):245–258

Macmanus D, Dean K, Iversen AC et al (2012) Impact of pre-enlistment antisocial behaviour on behavioural outcomes among UK military personnel. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47(8):1353–1358. doi:10.1007/s00127-011-0443-z (published online first: epub date)

Stata Statistical Software (2009) Release 11 [program]. Stata Corporation, College Station

Dom G, De Wilde B, Hulstijn W, Sabbe B (2007) Traumatic experiences and posttraumatic stress disorders: differences between treatment-seeking early- and late-onset alcoholic patients. Compr Psychiatry 48(2):178–185

Liebschutz J, Saitz R, Brower V et al (2007) PTSD in urban primary care: high prevalence and low physician recognition. J Gen Intern Med 22(6):719–726

Sullivan TP, Holt LJ (2008) PTSD symptom clusters are differentially related to substance use among community women exposed to intimate partner violence. J Trauma Stress 21(2):173–180

Seal KH, Cohen G, Waldrop A, Cohen BE, Maguen S, Ren L (2011) Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001–2010: implications for screening, diagnosis and treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend 116(1–3):93–101

Gillihan SJ, Farris SG, Foa EB (2011) The effect of anxiety sensitivity on alcohol consumption among individuals with comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Addict Behav 25(4):721–726

Johnson SD, Cottler LB, O’Leary CC, Ben Abdallah A (2010) The association of trauma and PTSD with the substance use profiles of alcohol- and cocaine-dependent out-of-treatment women. Am J Addict 19(6):490–495. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00075.x (published online first: epub date)

Taft CT, Kaloupek DG, Schumm JA et al (2007) Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, physiological reactivity, alcohol problems, and aggression among military veterans. J Abnorm Psychol 116(3):498–507

Cabrera O, Hoge C, Bliese P, Castro C, Messer S (2007) Childhood adversity and combat as predictors of depression and post-traumatic stress in deployed troops. Am J Prev Med 33(2):77–82

Scherrer JF, Xian H, Lyons MJ et al (2008) Posttraumatic stress disorder; combat exposure; and nicotine dependence, alcohol dependence, and major depression in male twins. Compr Psychiatry 49(3):297–304

Sartor CE, McCutcheon VV, Pommer NE et al (2011) Common genetic and environmental contributions to post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence in young women. Psychol Med 41(7):1497–1505

Chiu S, Niles JK, Webber MP et al (2011) Evaluating risk factors and possible mediation effects in posttraumatic depression and posttraumatic stress disorder comorbidity. Publ Health Rep 126(2):201–209

Drapkin ML, Yusko D, Yasinski C, Oslin D, Hembree EA, Foa EB (2011) Baseline functioning among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat 41(2):186–192. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2011.02.012 (published online first: epub date)

Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD (2000) Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 68(5):748–766

Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS (2003) Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 129(1):52–73

Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Johnson DR, Yehuda R, Charney DS (1993) Childhood physical abuse and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry 150(2):235–239

Cabrera OA, Hoge CW, Bliese PD, Castro CA, Messer SC (2007) Childhood adversity and combat as predictors of depression and post-traumatic stress in deployed troops. Am J Prev Med 33(2):77–82. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.019 (published online first: epub date)

Jakupcak M, Tull MT, McDermott MJ, Kaysen D, Hunt S, Simpson T (2010) PTSD symptom clusters in relationship to alcohol misuse among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans seeking post-deployment VA health care. Addict Behav 35(9):840–843

McDevitt-Murphy ME, Murphy JG, Monahan CJ, Flood AM, Weathers FW (2010) Unique patterns of substance misuse associated with PSTD, depression, and social phobia. J Dual Diagn 6(2):94–110. doi:10.1080/15504261003701445 (published online first: epub date)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Simon Wessely is the Civilian Consultant Advisor in Psychiatry to the British Army and Trustee of Combat Stress.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Head, M., Goodwin, L., Debell, F. et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol misuse: comorbidity in UK military personnel. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 51, 1171–1180 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1177-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1177-8