Abstract

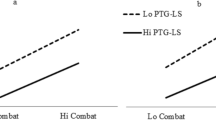

The impact of stress on mental health in high-risk occupations may be mitigated by organizational factors such as leadership. Studies have documented the impact of general leadership skills on employee performance and mental health. Other researchers have begun examining specific leadership domains that address relevant organizational outcomes, such as safety climate leadership. One emerging approach focuses on domain-specific leadership behaviors that may moderate the impact of combat deployment on mental health. In a recent study, US soldiers deployed to Afghanistan rated leaders on behaviors promoting management of combat operational stress. When soldiers rated their leaders high on these behaviors, soldiers also reported better mental health and feeling more comfortable with the idea of seeking mental health treatment. These associations held even after controlling for overall leadership ratings. Operational stress leader behaviors also moderated the relationship between combat exposure and soldier health. Domain-specific leadership offers an important step in identifying measures to moderate the impact of high-risk occupations on employee health.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:• Of importance, •• Of major importance

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. In: Milczarek M, editor. Emergency services: a literature review on occupational safety and health risks. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2011.

Skogstad M, Skorstad M, Conradi HS, Heir T, Weisæth L. Work-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Occup Med (Lond). 2013;63:175–82. Recent paper highlighting occupational groups at risk for exposure to traumatic events and PTSD. The paper includes a review of occupational groups not traditionally emphasized in occupationally-related PTSD research.

Perrin MA, DiGrande L, Wheeler K, Thorpe L, Farfel M, Brackbill R. Differences in PTSD prevalence and associated risk factors among World Trade Center disaster rescue and recovery workers. Am J Psychiatr. 2007;164:1385–94.

Neylan TC, Metzler TJ, Best SR, Weiss DS, Fagan JA, Liberman A. Critical incident exposure and sleep quality in police officers. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:345–52.

Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting D, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New Engl J Med. 2004;351:1–10.

Dohrenwend BP, Turner JB, Turse NA, Adams BG, Koenen KC, Marshall R. The psychological risks of Vietnam for U.S. veterans: a revisit with new data and methods. Science. 2006;313:979–82.

Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LE, McGurk D, Castro CA, Hoge CW. Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and national guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2010;614-23.

Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15(3):194–200.

Adler AB, Bliese PD, McGurk D, Hoge CW, Castro CA. Battlemind debriefing and battlemind as early interventions with soldiers returning from Iraq: randomization by platoon. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:928–40.

Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Fuller SR, Calhoun PS, Kinneer PM. Correlates of anger and hostility in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. Am J Psychiatr. 2010;167:1051–8.

McCarroll JE, Ursano RJ, Liu X, Thayer LE, Newby JH, Norwood AE, et al. Deployment and the probability of spousal aggression by U.S. army soldiers. Mil Med. 2000;165:41–4.

Wilk JE, Bliese PD, Kim PY, Thomas JL, McGurk D, Hoge CW. Relationship of combat experiences to alcohol misuse among U.S. soldiers returning from the Iraq war. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:115–21.

Riviere LA, Merrill JC. The impact of combat deployment on military families. In: Adler AB, Bliese PB, Castro CA, editors. Deployment psychology: evidence-based strategies to promote mental health in the military. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2011. p. 125–49.

Adler AB, Britt TW, Castro CA, McGurk D, Bliese PD. Effect of transition home from combat on risk-taking and health-related behaviors. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24:381–9.

Luxton DD, Greenburg D, Ryan J, Niven A, Wheeler G, Mysliwiec V. Prevalence and impact of short sleep duration in redeployed OIF soldiers. Sleep. 2011;34:1189–95.

Seelig AD, Jacobson IG, Smith B, Hooper TI, Boyko EJ, Gackstetter GD, et al. Sleep patterns before, during, and after deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan. Sleep. 2010;33:1615–22.

Smith TC, Ryan MA, Wingard DL, Slymen DJ, Sallis JF, Kritz-Silverstein D. New onset and persistent symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder self reported after deployment and combat exposures: prospective population based US military cohort study. Br Med J. 2008;336:366–71.

Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, Thomas JL, Hoge CM. Timing of post-combat mental health assessments. Psychol Serv. 2007;4:141–8.

Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW. Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298:2141–8.

Wolfe J, Erickson DJ, Sharkansky EJ, King DW, King LA. Course and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder among Gulf War veterans: a prospective analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:520–8.

Kim PY, Britt TW, Klocko RP, Riviere LA, Adler AB. Stigma, negative attitudes about treatment, and utilization of mental health care among soldiers. Mil Psychol. 2011;23:65–81.

Gould M, Adler A, Zamorski M, Castro C, Hanily N, Steele N, et al. Do stigma and other perceived barriers to mental health care differ across armed forces? A comparison of USA, UK, Australian, New Zealand and Canadian data. J R Soc Med. 2010;103:148–56.

Britt TW, Greene-Shortridge TM, Brink S, Nguyen QB, Rath J, Cox AL, et al. Perceived stigma and barriers to care for psychological treatment: implications for reactions to stressors in different contexts. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2008;27:317–35.

Hoge CW, Grossman SH, Auchterlonie JL, Riviere LA, Milliken CS, Wilk JE. PTSD treatment for soldiers after returning from Afghanistan: low utilization of mental health services and reasons for dropping out of care. Psychiatr Serv Adv. 2014. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201300307. Recent paper documenting reasons why soldiers do not pursue mental health care.

Lu MW, Duckart JP, O’Malley JP, Dobscha SK. Correlates of utilization of PTSD specialty treatment among recently diagnosed veterans at the VA. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:943–9.

Bliese PD, Castro CA. The Soldier Adaptation Model (SAM): applications to peacekeeping research. In: Britt TW, Adler AB, editors. Psychology of the peacekeeper: lessons from the field. Westport: Praeger Press; 2003. p. 185–203.

Adler AB, Castro CA. The Occupational Mental Health Model for the Military. Mil Behav Health. 2013;1:1–11. Provides a conceptual model and rationale for understanding the stressor-strain link from an occupational health perspective, particularly high-risk occupations like the military.

Kaiser RB, Hogan R, Craig SB. Leadership and the fate of organizations. Am Psychol. 2008;63:96–110.

Barling J, Christie A, Hoption A. Leadership. In: Zedeck S, editor. APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology Vol 1: building and developing the organization. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2011. p. 183–240.

Skakon J, Nielsen K, Borg V, Guzman J. Are leaders’ wellbeing, behaviours and style associated with the affective wellbeing of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work Stress. 2010;24:147–39.

Kelloway EK, Barling J. Leadership development as an intervention in occupational health psychology. Work Stress. 2010;24:260–79.

Bass BM. Leadership and performance beyond expectation. New York: Free Press; 1985.

Kuoppala J, Lamminpaa A, Liira J, Vainio H. Leadership, job well-being, and health effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;60:904–15.

Avolio BJ, Bass BM, Jung DI. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the multifactor leadership questionnaire. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1999;72:441–62.

Lyons JB, Schneider TR. The effects of leadership style on stress outcomes. Leadersh Q. 2009;20:737–48.

Arnold KA, Turner N, Barling J, Kelloway EK, McKee MC. Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: the mediating role of meaningful work. J Occup Health Psychol. 2007;12:193–203.

Halbesleben JRB. Sources of social support and burnout: a meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources model. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91:1134–45.

Barling AJ, Weber T, Kelloway EK. Effects of transformational leadership training on attitudinal and financial outcomes: a field experiment. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81:827–32.

Clarke S. Safety leadership: A meta-analytic review of transformational and transactional leadership styles as antecedents of safety behaviours. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2013;86:22–49. This recent review of transformational and transactional leadership underscores the importance of specific leadership behaviors for specific types of employee safety outcomes and organizational safety climate.

Zohar D, Tenne-Gazit O. Transformational leadership and group interaction as climate antecedents: a social network analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93:744–57.

Barling J, Loughlin C, Kelloway EK. Development and test of a model linking safety-specific transformational leadership and occupational safety. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87:488–96.

Mullen J, Kelloway EK, Teed M. Inconsistent style of leadership as a predictor of safety behavior. Work Stress. 2011;25:41–54.

Zohar D. The effects of leadership dimensions, safety climate, and assigned priorities on minor injuries in work groups. J Organ Behav. 2002;23:75–92.

Kelloway EK, Mullen J, Francis L. Divergent effects of transformational and passive leadership on employee safety. J Occup Health Psychol. 2006;11:76–86.

Newman S, Griffin MA, Mason C. Safety in work vehicles: a multilevel study linking safety values and individual predictors to work-related driving crashes. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93:632–44.

Hoffmeister K, Gibbons AM, Johnson SK, Cigularov KP, Chen PY. The differential effects of transformational leadership facets on employee safety. Saf Sci. 2014;62:68–78.

Griffin MA, Hu X. How leaders differentially motivate safety compliance and safety participation: the role of monitoring, inspiring, and learning. Saf Sci. 2013;60:196–202.

Kapp EA. The influence of supervisor leadership practices on perceived group safety climate on employee safety performance. Saf Sci. 2012;50:1119–24.

Xuesheng DU, Wenbiao SUN. Research on the relationship between safety leadership and safety climate in coalmines. Procedia Eng. 2012;45:214–9.

Mullen JE, Kelloway EK. Safety leadership: A longitudinal study of the effects of transformational leadership on safety outcomes. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2009;82:253–72.

Gurt J, Schwennen C, Elke G. Health-specific leadership: is there an association between leader consideration for the health of employees and their strain and well-being? Work Stress. 2011;25:108–27.

Golaszewski T, Hoebbel C, Crossley J, Foley G, Dorn J. The reliability and validity of an organizational health culture audit. Am J Health Stud. 2008;23:116–23.

Rhoades L, Eisenberger R. Perceived organizational support: a review of the literature. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87:698–714.

Lentino CV, Purvis DL, Murphy KJ, Deuster PA. Sleep as a component of the performance triad: the importance of sleep in a military population. In: The United States Army Medical Department Journal. 2013 Oct-Dec:98-108. http://www.cs.amedd.army.mil/FileDownloadpublic.aspx?docid=565febfe-b26e-4922-8f82-0e9373b5f01a. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

Abdullah SP. Performance triad to lead Army medicine to system for health. In: The Official Homepage of the United States Army. 2013. http://www.army.mil/article/93893/Performance_Triad_to_Lead_Army_Medicine_to_System_for_Health/. Accessed 19 Jun 2014.

Gunia BC, Sipos ML, LoPresti M, Adler AB. Sleep leadership in high-risk occupations: An investigation of soldiers on peacekeeping and combat missions. 2014. This paper illustrates the role that behavioral health leadership in the military plays in accounting for key indicators of well-being over and above general leadership.

Bliese PD. Social climates: drivers of soldier well-being and resilience. In: Adler AB, Castro CA, Britt TW, editors. Operational Stress. Westport: Praeger Security International; 2006. p. 213–34.

Castro CA, McGurk D. The intensity of combat and behavioral health status. Traumatol. 2007;13:6–23.

Wright KM, Cabrera OA, Bliese PD, Adler AB, Hoge CW, Castro CA. Stigma and barriers to care in soldiers postcombat. Psychol Serv. 2009;6:108–16.

Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Internatl Soc for Traum Stress Studies, San Antonio, 1993.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of self-report version of the PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1734–44.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the U.S. Army Medical Command or the US Army. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. Funding was received from the U.S. Army Military Operational Medicine Research Program. The authors report no competing interests. Thanks to Paul Kim for editorial assistance.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

Amy B. Adler, Kristin N. Saboe, James Anderson, Maurice L. Sipos, and Jeffrey L. Thomas declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Military Mental Health

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adler, A.B., Saboe, K.N., Anderson, J. et al. Behavioral Health Leadership: New Directions in Occupational Mental Health. Curr Psychiatry Rep 16, 484 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0484-6

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0484-6